Wildlife Seed Dispersal Impact Calculator

How Malaria Impacts Forest Regeneration

Based on the Amazon case study, malaria infection in seed-dispersing wildlife reduces reproductive success, which directly impacts forest regeneration. Enter your scenario to see the ecological consequences.

Malaria is a vector‑borne disease caused by Plasmodium parasites that primarily infect vertebrate blood cells. While most people think of human fever and chills, the parasite’s reach extends far beyond hospitals and into the wild. When you look at the bigger picture, you’ll see that malaria can ripple through animal populations, reshape food webs, and even alter how landscapes function.

Why Wildlife Matters in Malaria Transmission

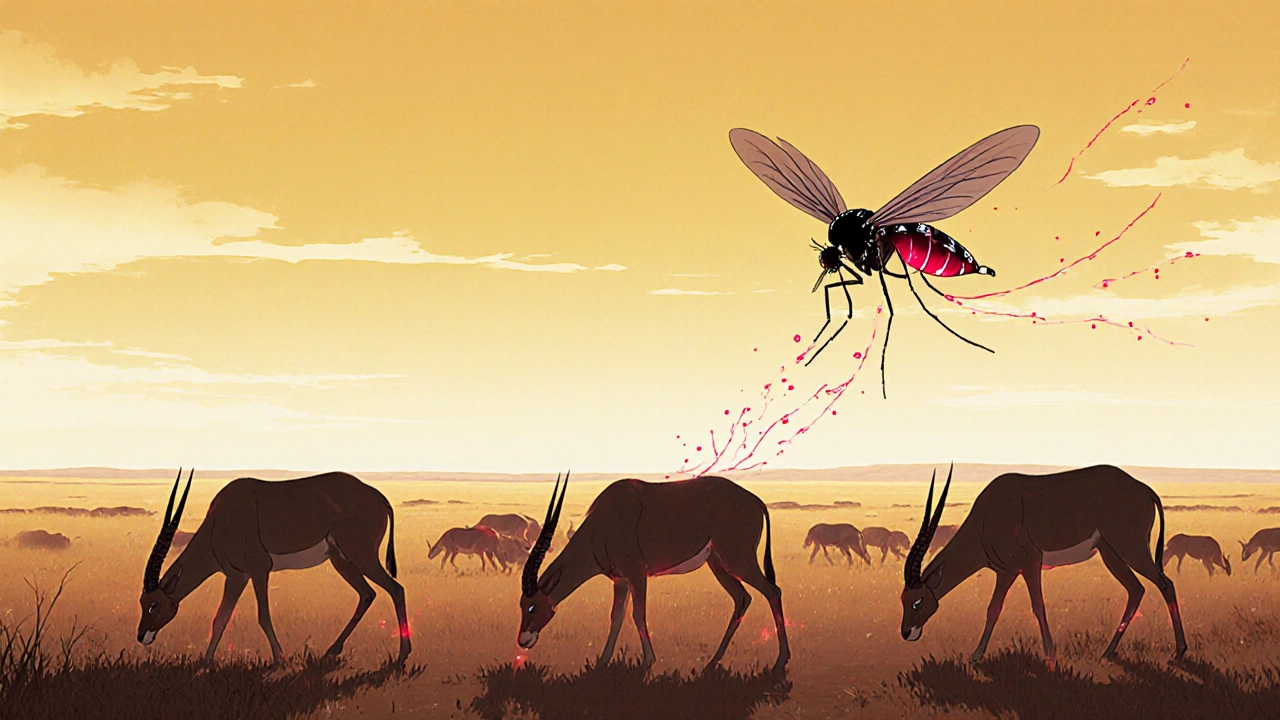

Wildlife refers to all non‑human organisms living in natural habitats. These animals are not just passive victims; they can act as reservoirs, amplifying hosts, or dead‑end hosts for the malaria parasite. In places like the African savanna, certain antelope species carry Plasmodium the malaria‑causing parasite without showing severe symptoms. Mosquitoes that bite these animals pick up the parasite and later transmit it to other wildlife or humans, creating a loop that ties health and ecology together.

The Mosquito Bridge: Anopheles Species

Not every mosquito can spread malaria. The Anopheles mosquito is the primary vector for Plasmodium parasites because its feeding habits align with the parasite’s life cycle. In forested regions, species like Anopheles gambiae prefer to feed on both humans and large mammals, making them efficient carriers across species boundaries. When environmental conditions favor mosquito breeding-standing water, warm temperatures-the risk of cross‑species transmission spikes.

Ecological Consequences of Wildlife Infection

When wildlife contracts malaria, the effects can be subtle but far‑reaching. Infected birds often exhibit reduced stamina, affecting their migration patterns and breeding success. This can lead to lower biodiversity the variety of life in an ecosystem, which in turn weakens ecosystem resilience. Predators that rely on healthy prey may find fewer food sources, altering predator‑prey dynamics the interactions between hunting species and their targets. Over time, these shifts can change vegetation patterns, nutrient cycling, and even the frequency of wildfires.

Case Study: Malaria in Amazonian Wildlife

Researchers exploring the Amazon have documented malaria infections in howler monkeys, capuchin monkeys, and certain bat species. These mammals serve as reservoirs for Plasmodium, which then jumps to local mosquito populations. The result? A measurable drop in monkey reproductive rates during peak infection periods. As monkey numbers decline, seed dispersal-a key forest regeneration service-slows down, leading to slower tree growth and altered canopy structure.

Climate Change: Amplifying the Threat

Rising temperatures expand the geographic range of climate change the long‑term shift in weather patterns-driven mosquito habitats. Areas once too cool for Anopheles now support year‑round breeding, introducing malaria risk to high‑altitude wildlife that has never faced the disease. This new exposure can cause unexpected mortality spikes, especially in species with limited genetic resistance.

Conservation Strategies to Break the Cycle

Addressing malaria’s ecological impact requires a blend of public health and wildlife management. Conservation efforts aimed at protecting species and habitats groups are increasingly integrating vector control into protected‑area plans. Some strategies include:

- Restoring natural water flow to reduce stagnant pools where mosquitoes breed.

- Introducing larvivorous fish in wetland habitats to eat mosquito larvae.

- Using targeted insecticide‑treated netting around high‑risk wildlife watering holes.

- Monitoring wildlife health through blood sampling to detect early Plasmodium outbreaks.

Policy and Research Gaps

Many national wildlife agencies still treat malaria as a human health issue, leaving a blind spot for its ecological ramifications. Funding for interdisciplinary studies that combine epidemiology, ecology, and climate science remains limited. Bridging this gap means encouraging joint grants, creating shared data platforms, and training a new generation of “disease ecologists” who can move fluidly between lab and field.

Key Takeaways

- Wildlife can act as reservoirs for malaria, influencing both animal and human health.

- Infected animals experience reduced fitness, which can cascade through food webs and affect ecosystem functions.

- Climate change expands mosquito habitats, exposing new wildlife populations to malaria.

- Integrated conservation and vector‑control measures are essential for breaking the disease‑ecosystem feedback loop.

- Policy must evolve to fund cross‑disciplinary research that treats malaria as both a health and ecological challenge.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can malaria really kill wildlife?

Yes. While many wild animals tolerate low‑level infections, severe cases can cause anemia, weight loss, and death, especially in young or stressed individuals.

Which animal groups are most affected?

Primates, certain bird species, and some small mammals like rodents are frequently reported as malaria hosts in tropical regions.

How does malaria alter ecosystem services?

When key seed‑dispersing animals decline, forest regeneration slows. Reduced pollinator health can affect plant reproduction, and predator‑prey imbalances may change herbivore pressure on vegetation.

What role does climate change play?

Warmer temperatures and altered rainfall patterns create new breeding sites for Anopheles mosquitoes, pushing malaria into higher elevations and latitudes previously free of the disease.

Are there practical steps for conservationists?

Yes. Habitat restoration, targeted larval control, health monitoring of key species, and collaboration with public‑health agencies are all proven measures.

barnabas jacob

October 20, 2025 AT 20:22The zoonotic spillover risk posed by malaria is not just a human health nuisance; it's a systemic failure of our ecological stewardship, a clear case of anthropogenic externalities that we can no longer ignore. Every time we let stagnant water persist in a savanna or a wetland, we are effectively subsidizing vector proliferation, which in turn acts as a conduit for Plasmodium to infiltrate wildlife reservoirs. This cascade of infection leads to reduced fitness in keystone species, undermining trophic stability and jeopardizing the very services ecosystems provide-services that humans rely on for food, clean water, and climate regulation. It's definatly time for a paradigm shift, from treating malaria as a human-only problem to recognizing its cross‑species impact and acting accordingly. The moral imperative is crystal clear: we must intervene now, before the ecological debt becomes insurmountable.

jessie cole

October 24, 2025 AT 11:08Dear readers, the breadth of this article is truly commendable, and I applaud the effort poured into elucidating the hidden links between malaria and ecosystem health. Your thorough exposition of vector dynamics demonstrates a profound understanding that many researchers still lack. It is evident that the scientists involved have navigated complex field data with unwavering dedication, and that deserves our highest respect. The narrative captures the delicate balance of predator‑prey relationships and how a microscopic parasite can unsettle that equilibrium. By highlighting the Amazonian case study, you have painted a vivid picture of how seed dispersal can falter when primates are afflicted. This connection between disease and forest regeneration is often overlooked, yet you have made it unmistakably clear. Moreover, the discussion of climate change as an amplifying force provides essential context for future risk assessments. Your call for integrated conservation and public‑health strategies is both visionary and actionable. It encourages policymakers to break down silos and foster interdisciplinary collaborations, a step that is long overdue. The emphasis on monitoring wildlife health through blood sampling is pragmatic and reinforces the need for early detection systems. I also appreciate the balanced tone that neither sensationalizes nor downplays the seriousness of the threat. The inclusion of practical measures, such as restoring natural water flow and introducing larvivorous fish, offers concrete pathways for on‑the‑ground implementation. Readers are left with a sense of empowerment, knowing that tangible actions can mitigate this cascading problem. Your article stands as a beacon for how scientific communication should be conducted: clear, compassionate, and compelling. In light of these strengths, I encourage fellow scholars to build upon this foundation and broaden the scope of research to include even more taxa. Let us all commit to safeguarding both human health and the vitality of our planet’s ecosystems.

Deja Scott

October 28, 2025 AT 00:54The interplay between disease ecology and cultural practices is often subtle, yet it shapes how communities respond to health threats. In many regions, traditional knowledge about mosquito habitats can inform modern control measures, bridging science and heritage. Recognizing these connections enriches our approach to conservation, ensuring that interventions respect local values while protecting biodiversity. This perspective underscores the importance of inclusive research that honors both ecological and cultural dimensions.

Natalie Morgan

October 31, 2025 AT 15:41Cool insight on how malaria reshapes ecosystems

Mahesh Upadhyay

November 4, 2025 AT 06:27Malaria in wildlife is a stark reminder that nature does not grant us immunity from our own disruptions. The drama of infected birds faltering mid‑flight exemplifies this tragedy. Our moral duty is to curb mosquito breeding sites before the damage spreads further. Ignoring this risk only deepens the ecological wound.

Rajesh Myadam

November 7, 2025 AT 21:13I understand the frustration that comes with seeing species suffer from a disease we can help control. It’s encouraging to see suggestions like larval fish introduction; these are realistic steps that communities can adopt. Let’s keep sharing such practical ideas and support each other in implementing them.

laura wood

November 11, 2025 AT 11:59It’s heart‑warming to read about the dedication of researchers working to protect both animal health and ecosystem services. Their efforts remind us that compassion for wildlife ultimately benefits humanity as well. Supporting these initiatives is a responsibility we all share.

Kate McKay

November 15, 2025 AT 02:45Great job highlighting the need for interdisciplinary collaboration. By bringing together epidemiologists, ecologists, and local stakeholders, we can develop holistic solutions that address both disease control and habitat preservation. Keep championing these connections, and the impact will only grow.

Demetri Huyler

November 18, 2025 AT 17:31While many Western scholars chase trendy topics, it is the pragmatic American conservation model that truly sets the benchmark for effective malaria management. Our robust funding mechanisms and cutting‑edge technology give us an edge that others merely aspire to. It is no surprise that the U.S. leads in integrating vector control with wildlife preservation, a testament to our national ingenuity.

JessicaAnn Sutton

November 22, 2025 AT 08:18The argument presented overlooks the ethical responsibility of affluent nations to aid less‑privileged regions in combating malaria’s ecological toll. Ignoring this duty perpetuates a cycle of exploitation and environmental degradation. A rigorous, morally sound approach must include equitable resource distribution and collaborative research.

Israel Emory

November 25, 2025 AT 23:04Indeed, the complexities of malaria transmission require a nuanced perspective, and I appreciate the thorough analysis provided, yet we must also consider the socioeconomic variables that influence vector habitats, such as land‑use change, urbanization, and agricultural practices, all of which demand coordinated policy responses, and only through inclusive dialogue can we hope to devise sustainable solutions.

Sebastian Green

November 29, 2025 AT 13:50I feel the weight of these ecological challenges, and I stand with those working tirelessly to protect vulnerable species.

Wesley Humble

December 3, 2025 AT 04:36From a phyto‑epidemiological standpoint, the data unequivocally demonstrate that vector control interventions yield quantifiable reductions in wildlife morbidity, as evidenced by longitudinal studies across multiple biomes. Furthermore, the integration of remote sensing technologies enhances our capacity to predict outbreak hotspots with unprecedented accuracy. Consequently, stakeholders should allocate resources toward these evidence‑based strategies to maximize ecological resilience. 📊📚

Kirsten Youtsey

December 6, 2025 AT 19:22One cannot help but notice that the previous exposition conveniently aligns with mainstream funding agendas, masking the underlying agenda of power consolidation within elite research circles. Such selective presentation raises doubts about the impartiality of the conclusions drawn, suggesting that further scrutiny is warranted.