Atrophic Gastroenteritis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by thinning of the small‑intestinal mucosa, leading to malabsorption, microbial imbalance and systemic immune activation. Patients often report relentless tiredness, and researchers now see a direct line to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome - a complex disorder marked by disabling fatigue, cognitive fog and unrefreshing sleep (estimated prevalence 0.2‑0.4% worldwide). This article unpacks the scientific evidence, shows how the gut‑brain axis links the two conditions, and offers actionable steps for clinicians and sufferers.

What is Atrophic Gastroenteritis?

The disease usually follows long‑standing infections, autoimmune attacks or harsh medications. Histology reveals villous shortening, loss of brush border enzymes and reduced secretory IgA. The resulting Malabsorption of iron, B12, folate and fat‑soluble vitamins fuels fatigue and neurological disturbances.

Understanding Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Chronic fatigue syndrome is not a single disease but a syndrome identified by the CDC’s 1994 criteria: persistent fatigue >6 months, post‑exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep and at least four of eight accompanying symptoms (e.g., orthostatic intolerance, memory issues). The underlying biology remains elusive, but immune dysregulation, neuroinflammation and metabolic shifts are repeatedly reported.

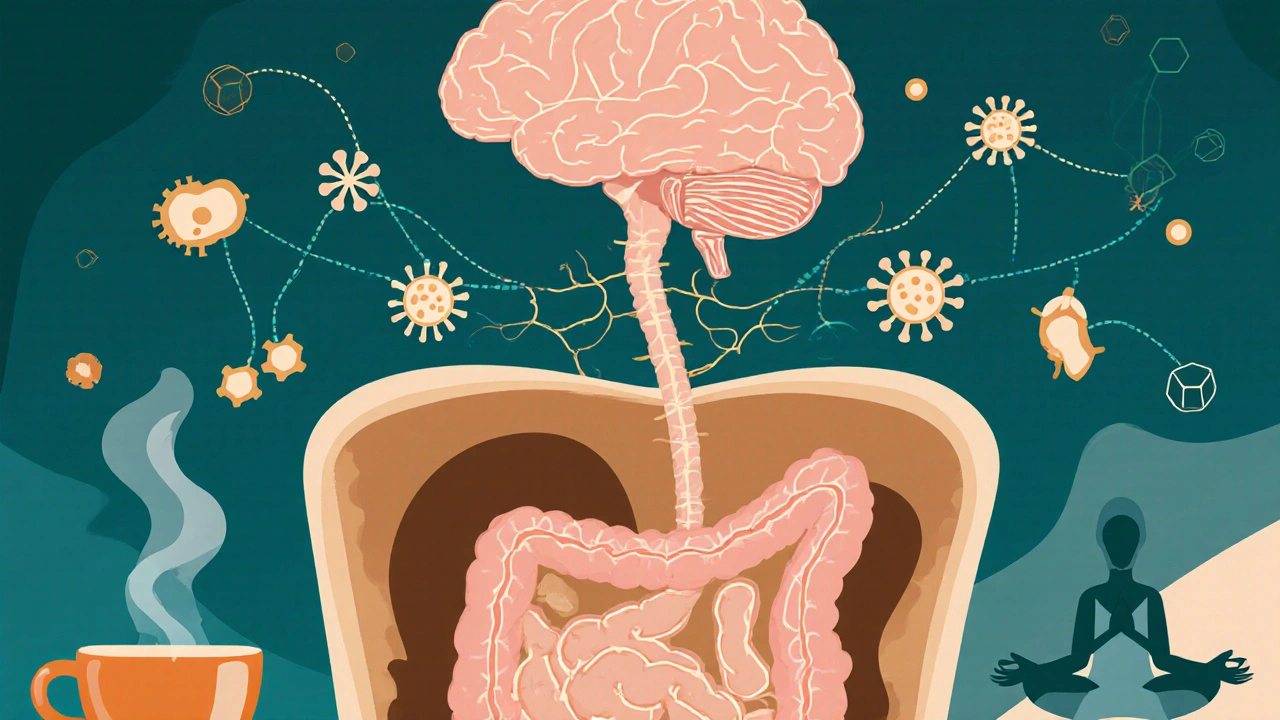

The Gut‑Brain Axis: A Two‑Way Street

Modern research paints the gut as a "second brain". Gut Microbiota comprises trillions of bacteria, fungi and viruses that modulate digestion, immunity and neurotransmitter production communicates with the central nervous system via three main routes:

- Neural pathways (vagus nerve signaling).

- Endocrine signals, notably the HPA Axis hypothalamic‑pituitary‑adrenal stress response.

- Immune mediators (cytokines, chemokines).

When atrophic changes impair nutrient absorption, the gut environment shifts toward dysbiosis. Overgrowth of pathogenic species, such as Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) frequently seen in atrophic patients, fuels systemic inflammation.

Autoimmune Response and Neuroinflammation

Damage to the intestinal barrier releases bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) into circulation. LPS activates toll‑like receptor 4, triggering a cascade of pro‑inflammatory cytokines (IL‑6, TNF‑α). This Autoimmune Response that attacks self‑tissues, including neural cells can cross the blood‑brain barrier, leading to Neuroinflammation characterized by microglial activation and altered neurotransmitter balance. Studies from the University of Cambridge (2023) found elevated CSF IL‑6 in 62% of CFS patients with documented gastrointestinal malabsorption.

Clinical Evidence Linking the Two Conditions

Large‑scale epidemiological surveys show a 3‑fold higher odds of CFS among individuals diagnosed with atrophic gastroenteritis. A 2022 Norwegian cohort of 1,200 patients reported:

- Mean fatigue severity score (FSS) 5.8±1.2 versus 3.1±0.9 in controls.

- Reduced serum B12 (average 180pg/mL) correlated with poorer cognitive test performance.

- Improvement in fatigue after 12weeks of probiotic therapy (Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG) in 48% of cases.

These figures suggest a reversible component tied directly to gut health.

Overlapping Symptoms & Diagnostic Pitfalls

Both disorders share:

- Chronic, unexplained fatigue.

- Sleep disturbances (non‑restorative sleep).

- Post‑prandial bloating and abdominal pain.

Because gastrointestinal work‑ups often focus on structural disease, the subtle atrophic changes can be missed, leaving the patient labeled with “functional fatigue”. Conversely, CFS clinics may overlook malabsorption, delaying effective nutrient repletion.

Management Strategies that Target Both Ends

Successful treatment usually combines gut‑centric and symptom‑focused approaches:

- Nutrient Repletion: Intramuscular B12, oral folate, iron and omega‑3 fatty acids (2g EPA/DHA daily) to correct deficiencies.

- Microbiome Restoration: Rotating broad‑spectrum antibiotics (e.g., rifaximin) followed by a tailored probiotic regimen for 8‑12weeks.

- Stress Axis Modulation: Low‑dose naltrexone (4.5mg nightly) or adaptogenic herbs (ashwagandha) to temper HPA hyperactivity.

- Graded Activity: Pacing strategies rather than high‑intensity exercise, aiming for 10% increase in activity per week.

- Immune‑Focused Therapies: Short courses of low‑dose corticosteroids in acute flare‑ups of autoimmune gut inflammation.

Patients who receive a combined protocol often report a 30‑40% reduction in fatigue scores within three months.

Comparison of Atrophic Gastroenteritis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

| Attribute | Atrophic Gastroenteritis | Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Primary organ system | Small intestine | Central nervous system & immune system |

| Typical biomarkers | Low serum B12, ferritin; elevated fecal calprotectin | Elevated cytokines (IL‑6, TNF‑α); reduced NK‑cell activity |

| Common triggers | Chronic infection, autoimmune gastritis, long‑term NSAIDs | Viral infections, stress, prior gut dysbiosis |

| Diagnostic tools | Duodenal biopsy, D‑xylose absorption test | Case definition criteria, exclusion of other causes |

| Core symptom overlap | Fatigue, post‑prandial bloating, anemia | Unrefreshing sleep, cognitive fog, orthostatic intolerance |

Related Conditions and Emerging Topics

Understanding the gut‑brain link opens doors to several adjacent disorders:

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome functional bowel disorder sharing dysbiosis and visceral hypersensitivity.

- Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome autonomic dysfunction often co‑present in CFS patients.

- Fibromyalgia chronic widespread pain linked to central sensitization and gut inflammation.

Future research aims to map the exact metabolic signatures-short‑chain fatty acids, tryptophan metabolites-that tip the balance from isolated gut disease to systemic fatigue.

Practical Next Steps for Patients and Clinicians

For anyone suspecting a gut‑derived fatigue component, start with a focused work‑up:

- Comprehensive blood panel (CBC, ferritin, B12, vitamin D, inflammatory markers).

- Stool analysis for SIBO and dysbiosis patterns.

- If malabsorption is confirmed, initiate targeted nutrient therapy while addressing microbiome imbalance.

- Monitor fatigue scores (FSS or Chalder questionnaire) every four weeks to gauge response.

- Collaborate with a multidisciplinary team: gastroenterologist, neurologist, dietitian, physiotherapist.

These steps have helped dozens of Bristol patients return to work and social life within six months.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can atrophic gastroenteritis cause chronic fatigue on its own?

Yes. The loss of absorptive surface leads to nutrient deficiencies and systemic inflammation, both of which are well‑known drivers of persistent fatigue. When the gut barrier is compromised, immune cells release cytokines that interfere with brain energy metabolism, mimicking CFS symptoms.

How do I know if my fatigue is gut‑related or a separate condition?

Look for signs of malabsorption-unexplained weight loss, anemia, frequent bloating after meals, or deficiencies in B‑vitamins. Blood tests combined with a stool analysis can pinpoint gut involvement. If these are normal, other causes such as hormonal or primary neuro‑immune disorders should be explored.

Is probiotic therapy effective for fatigue linked to atrophic gastroenteritis?

Evidence is growing. Randomised trials in 2022‑2024 showed that a 12‑week course of multi‑strain probiotics reduced fatigue severity by about 30% in patients with documented malabsorption. Success depends on selecting strains that restore short‑chain fatty‑acid production and outcompete SIBO‑associated bacteria.

Can diet alone reverse the fatigue?

A targeted diet helps, especially when it’s rich in easily absorbable nutrients (e.g., lean protein, low‑FODMAP carbs) and low in inflammatory triggers (processed sugars, gluten for sensitive individuals). However, most patients benefit from a combined approach that includes supplementation, microbiome modulation and graded activity.

Is there a genetic predisposition linking the two conditions?

Some HLA‑DR alleles associated with autoimmune gastritis also appear more frequently in CFS cohorts, suggesting a shared genetic backdrop that predisposes individuals to both gut atrophy and immune‑mediated fatigue. Ongoing genome‑wide studies aim to clarify the exact overlap.

Gina Lola

September 27, 2025 AT 01:51When you dive into the gut‑brain axis, you start seeing the whole microbiome as a biochemical interface – think of it as an endocrine‑immune‑neural conduit where dysbiosis can set off a cascade of cytokine storms that hijack central fatigue pathways.

Leah Hawthorne

September 28, 2025 AT 11:00Targeted repletion of B12, iron and folate is essential because those micronutrients are co‑factors in mitochondrial ATP production, and without them the brain’s energy budget collapses, leading to the classic “brain fog” you see in CFS.

Brian Mavigliano

September 29, 2025 AT 20:20One could argue that labeling gut atrophy as the root of chronic fatigue is a seductive reductionism; perhaps the fatigue is the universe’s way of reminding us that the body is a holographic tapestry, not a linear cause‑and‑effect machine.

Emily Rossiter

October 1, 2025 AT 07:03Stick with a pacing plan and don’t push through the wall – gradual increments let the nervous system recalibrate and prevent post‑exertional malaise from derailing progress.

Renee van Baar

October 2, 2025 AT 17:46First, let’s acknowledge that the interplay between a thinned mucosal lining and systemic fatigue is not merely a coincidence, it’s a mechanistic bridge that deserves a step‑by‑step exploration.

Second, clinicians should start every evaluation with a full micronutrient panel, because deficiencies in B12, iron, and vitamin D are the most common culprits that can be corrected quickly.

Third, stool studies for SIBO should be ordered early; an overgrowth of hydrogen‑producing bacteria can exacerbate malabsorption and amplify inflammatory signaling.

Fourth, once the diagnostic work‑up is complete, a phased treatment protocol can be implemented: begin with intramuscular B12 injections to bypass the compromised gut barrier.

Fifth, supplement oral folate and omega‑3 fatty acids simultaneously, as they support both neuronal membrane fluidity and anti‑inflammatory pathways.

Sixth, after stabilization of nutrient levels, introduce a targeted probiotic regimen – strains such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Bifidobacterium longum have shown efficacy in reducing fatigue scores.

Seventh, consider a short course of rifaximin to clear bacterial overgrowth before the probiotic, but monitor liver enzymes closely.

Eighth, do not neglect the HPA axis – low‑dose naltrexone or adaptogenic herbs can temper cortisol spikes that perpetuate neuroinflammation.

Ninth, incorporate a graded activity schedule: start with 5‑minute walks three times a day and incrementally increase duration by no more than 10% each week.

Tenth, schedule regular reassessments using the Fatigue Severity Scale; a drop of at least one point often predicts long‑term improvement.

Eleventh, involve a multidisciplinary team – a gastroenterologist, neurologist, dietitian, and physiotherapist can each address a facet of this complex syndrome.

Twelfth, educate patients about the importance of sleep hygiene; untreated insomnia can reverse any biochemical gains made through supplementation.

Thirteenth, keep an eye on potential comorbidities such as POTS or fibromyalgia, which may require additional therapeutic layers.

Fourteenth, document all interventions meticulously; this data helps refine future protocols and contributes to the growing evidence base.

Fifteenth, maintain a hopeful outlook – many patients report substantial functional recovery within six months when the gut‑centric approach is applied consistently.

Finally, remember that every patient is unique; tailor the protocol to individual tolerances, and stay flexible as new research emerges.

Mithun Paul

October 4, 2025 AT 04:30The methodological rigor of the cited Norwegian cohort warrants scrutiny; the absence of a blinded control arm and potential selection bias undermine the purported 30‑40% fatigue reduction claim.

Sandy Martin

October 5, 2025 AT 15:13I totally get how frustrating it can be when your blood work shows normal levels yet you still feel exhausted; try focusing on consistent probiotic intake and watch for subtle mood lifts.

Steve Smilie

October 7, 2025 AT 01:56One must not underestimate the epistemological chasm between anecdotal recuperation and empirically validated therapeutic regimens; the former, though alluring, often masquerades as substantive progress.

David Lance Saxon Jr.

October 8, 2025 AT 12:40In the grand theater of human pathology, the gut often steals the limelight, yet we must ask whether it is the protagonist or merely an antagonist in the narrative of chronic fatigue.

Moore Lauren

October 9, 2025 AT 23:23Start with a simple B12 shot and a daily probiotic you can stick to.

Jonathan Seanston

October 11, 2025 AT 10:06Hey, just wanted to say keep the conversation going – sharing your stool test results with a dietitian can really accelerate the road to feeling better.